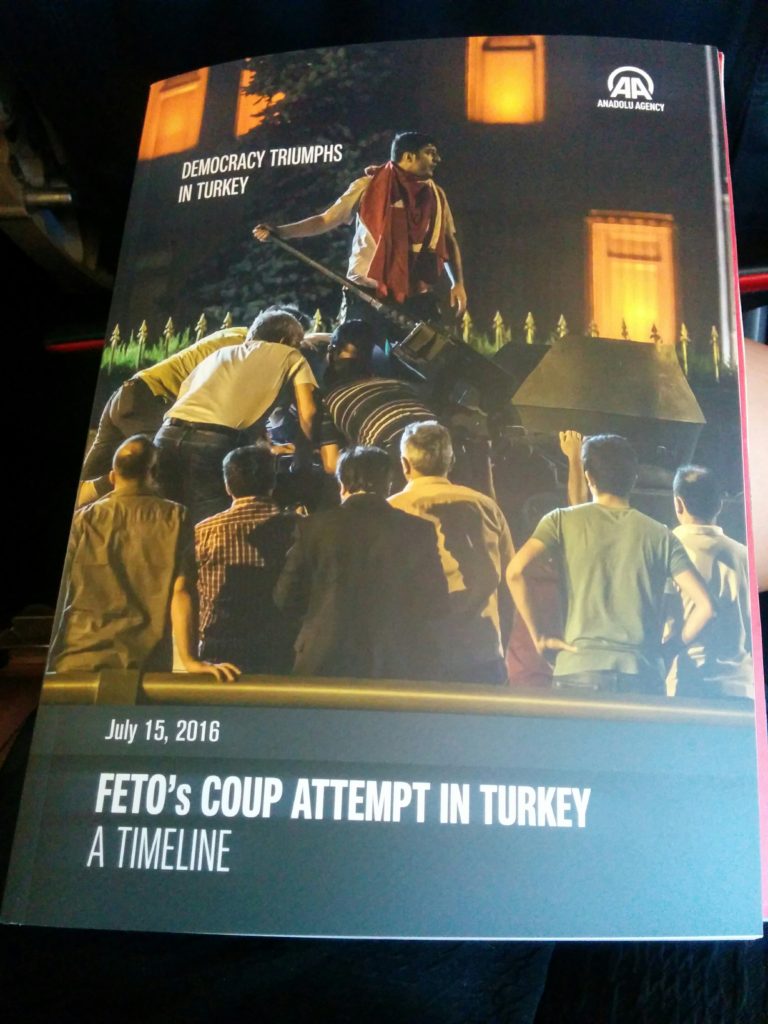

Part of the Turkish Airlines flight to Bosnia was spent perusing a glossy propaganda magazine explaining the recent failed coup and its perpetrators’ alleged American connections — every passenger gets a copy.

After a quick stop at the Istanbul airport, we were on our way to Sarajevo to meet our friends John and Ines from San Francisco.

John and Ines were just embarking on their own extended trip, starting with a visit to Ines’ family in Bosnia (where she grew up), so we figured we’d take advantage of the opportunity to see them and learn more about the country from an (ex-)local’s perspective. Thanks to Jines for being such great hosts!

We got in at night, and the next morning we were stunned by the beautiful views of Sarajevo across the narrow valley.

This picture just doesn’t do it justice; Sarajevo was probably the most charmingly picturesque capital we had visited thus far.

A short walk down the hill, next to the river at the base of the valley, we found ourselves in Baščaršija, Sarajevo’s cultural center, built by the Ottomans in the 15th century.

At the open center of Baščaršija is ‘Pigeon Square’, where several busy vendors sell pigeon food to crazy tourists all day long.

The square is surrounded by restaurants, and over the course of our stay we got to try a wide variety of dishes, from meat-inside-bread-with-cream-sauce (this one is called burek.):

to … well, you get the idea (this one is called ćevapi.):

From a bridge over the nearby Miljacka River, we could see a mixture of small mosques and churches blanketing the valley.

Bosnia is made up of three major ethnic groups with different religious associations: about half are Bosniaks (Muslim), and most of the rest are either Serbs (Orthodox Christian) or Croats (Catholic). In addition, there are growing Turkish influences, as well as an increasing number of visitors from Saudia Arabia and other Middle Eastern countries.

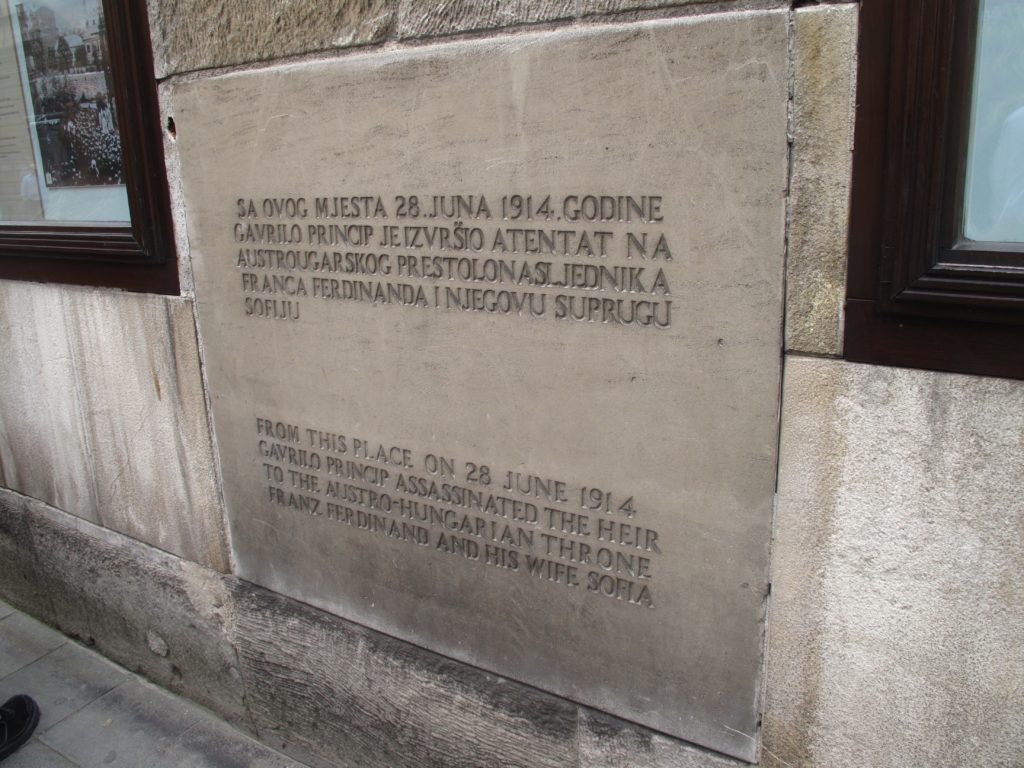

Just up the street from the bridge, our friends showed us this plaque marking the place where Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, precipitating the first World War.

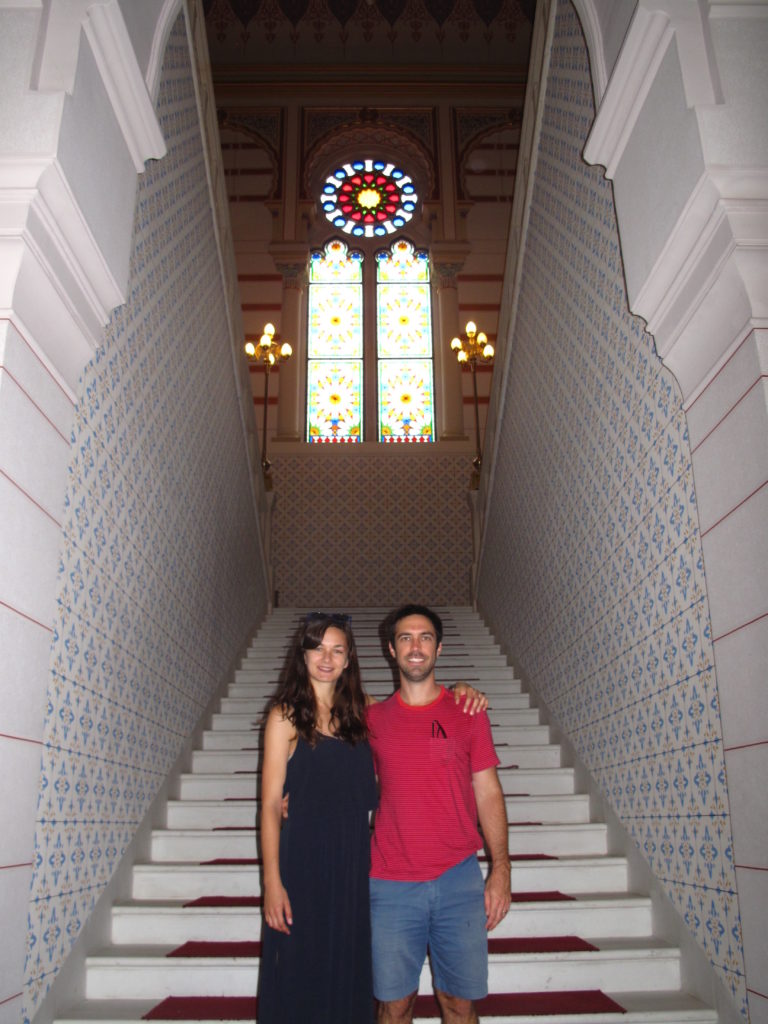

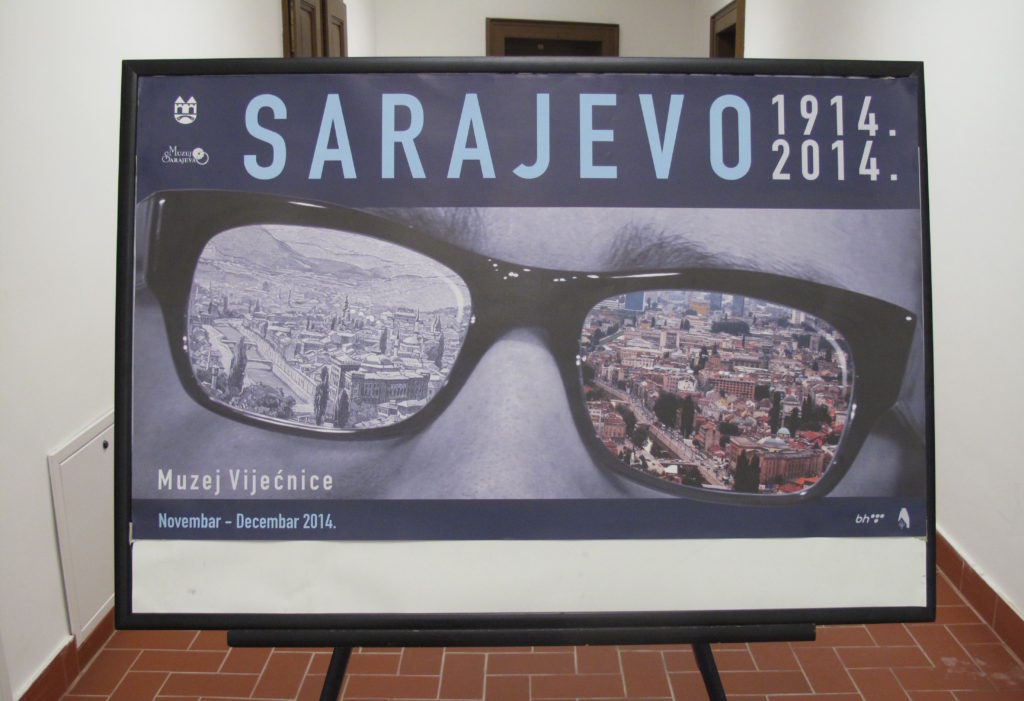

At the nearby Vijećnica (Sarajevo City Hall and National Library),

we attended an exhibit where we learned more about Sarajevo’s history, and the political, religious, and cultural factors and chain of events leading to Ferdinand’s assassination and then, ultimately, the devastating Bosnian war of the 1990s.

After Slovenia and Croatia gained their independence from Yugoslavia in 1991, the Bosniak-lead parliament passed a similar “Memorandum on the Sovereignty of Bosnia-Herzegovina” with opposition from the Bosnian Nationalist Serbs. This conflict ultimately grew into a war pitting the Bosnian Serbs, assisted by the military of Serbia, against the Bosniaks and Croats, with mass violence against civilians largely perpetrated by the Serbs (as far as we understand the very complicated conflict).

Around 100,000 people were killed during the war, and much of Sarajevo was destroyed in the siege by the Serbs, who fired artillery and sniper rifles into the city for nearly four years from the surrounding hillsides.

The library (and nearly two million of its books) was destroyed by artillery during the conflict; this picture shows the Cellist of Sarajevo performing in the ruins in 1992, near the beginning of the Siege. Vedran played Albinoni’s Adagio in G Minor for 22 days in a row to commemorate the 22 people who were killed by Serb forces while they were waiting in line for bread.

(credit Mikhail Evstafiev)

While the library has been beautifully rebuilt,

Signs of the conflict were still everywhere, from graveyards spotting the hillsides (credit Michael Büker):

to “Sarajevo Roses” (sidewalk damage from mortar shells, filled with red resin to signify that someone died from the blast),

to Soviet-era apartment buildings whose facades were still peppered with bullet holes from sniper fire.

We had both, of course, learned about the war in middle school, but quickly realized we didn’t really understand the gravity of it until we visited. Upon first arriving in beautiful Sarajevo, it was hard to believe there was a war here so relatively recently. But whenever we talked to a Bosnian for longer than five minutes, the effects of the war become painfully obvious. People often talked about widespread PTSD, land mines, and the continuing social divisions. However, as obvious as the scars of the war were, so was the resilience, creativity, and kindness of Bosnia’s people.

We spent one of our last evenings in Sarajevo at Ines’ parents’ house, where Ines cooked us a delicious traditional Bosnian meal. We had a lovely time catching up, meeting her friends and family, and looking at adorable pictures of a young Ines.

Afterwards, we went on a hike up the nearby Mojmillo Hill, when Jason’s knee suddenly gave out, and we had to catch a cab back home (fortunately, it’s been fine since).

Our last day in Bosnia, we went on a picturesque hiking tour to a small mountain village called Lukomir, which is colonized by sheep herders in the summer and completely cut off from civilization by snow in the winter.

On the three-hour hike down the canyon, we appreciated the stunning views of the countryside, while learning more about Bosnia from our excellent guide Sabina. She told us about how Bosnian soldiers would take refuge in small villages like Lukomir (which means ‘Peace Harbor’) to recuperate after being wounded. The village was supposed to be destroyed by Serbs (like 13 nearby villages were) but was thankfully spared.

The town, which is mostly composed of descendants of the Comor family,

also featured a mosque and a cemetery,

just next to some monumental medieval tombstones (called stecci) strewn about on the grass (a remnant of the Church of Bosnia before the Turks invaded).

On our way out, we ate some more meat pie and drank giant servings of fresh sheep’s milk,

and got one last glimpse of the flock.

The next day, we had a 9-hour train ride northwards to Croatia — our first train border crossing!

loved reading this Reed 🙂 hugs from Zurich 🙂

Thanks, I loved to read this! My good friend Tamara was in Bosnia and lived through the war ages 12-16. It was quite devastating, and I agree that we did not know nearly the extent of the atrocities including the fact that children were shipped out of Bosnia for their safety, only to be adopted out to families in nearby countries like Italy. Tamara’s research paper was on this and apparently quite dangerous work since there was/is a big cover up by the government.