It’s nearly 9am and we were expecting to be picked up an hour ago to drive to the eastern border of Ethiopia for a tour of the Danakil Depression. When the driver, Mebratu, finally shows up, we find out the reason for the tardiness is a flat tire. He shows us the offending donut, a misshapen threadbare tube that looks about 20 years old. While the replacement tire looked only marginally better, we were glad the first tire went flat before we took off.

We spent the next nine hours driving through charming grassland landscapes, full of striking geology, iconic acacia trees, farming communities struggling with the recent drought, lively Ethiopian wedding celebrations, and an uncountable number of goats.

Mebratu was a fun-loving guy who spoke better Italian than English. In the middle of the trip, we stopped unexpectedly in a small village near Robit (which we would find out later is the home of tej, Ethiopian honey wine). Mebratu called a young boy over, they exchanged a few words, and the boy picked up a flattened empty plastic bottle from the side of the road. The boy took the cap off, blew in the bottle to re-inflate it, and ran off to a shack nearby.

He returned with the bottle, now filled with a thick brown substance with lots of questionable darker brown chunks. We were then a bit dismayed when Mebratu passed the bottle to us and told us to drink it. Earlier on the drive, we told him that we hadn’t yet tried tej (while in Ethiopia), and since he was nice enough to buy us some, we didn’t want to seem ungrateful. So we took a few timid sips while he watched us, amused. It actually tasted way better than the tej we had drunk in the US, but both of us were a bit too freaked out by the unknown origin and weird pieces of foreign matter to drink much of it.

We arrived to the tour’s starting point, Mekele, in the late evening and fell asleep wondering what to do with the rest of the honey wine (spoiler alert: we left it in the hotel room). The next morning we met up with the rest of the group: 6 Ethiopians, 2 Canadians, 3 Brits, 2 Dutch, 1 Italian, 2 South Koreans, 1 Japanese, 2 Germans, and 2 fellow Americans.

We would spend the next four days driving in a caravan of cars through the surreal scenery and small villages of the Danakil Depression. The Danakil Depression is considered the hottest place on earth (with average annual temperatures of 34C, or 93F) and one of the lowest (dipping to 100m below sea level). It makes up the northern part of the Afar Depression, a junction of three tectonic plates that is home to the earliest hominins (like the ~4 million-year-old Ardi), as well as one of the world’s six lava lakes (on a volcano named Erta Ale). We couldn’t wait to get started!

On our drive, we saw lots of scenes like this:

When driving through the villages, we were always greeted by groups of children yelling ‘Ferengis!’ (what Ethiopians call foreigners) or sometimes ‘China!’ (the Chinese are investing large sums of money into building Ethiopian infrastructure).

We were especially drawn to this shy kid named Abdul.

We spent most of the day riding at a snail’s pace over rough, dusty terrain (we covered eighty kilometers in six hours), and finally arrived at Dodom, a small army outpost at the base of the Erta Ale volcano and about twenty kilometers from Eritrea’s border. The army post was established a few years ago after the Afar Revolutionary Democratic Unity Front (ARDUF) kidnapped a group of tourists, as part of their overall aim to unite all Afar people under one flag. ARDUF’s actions take place in the context of a complicated and volatile history between Eritrea and Ethiopia. Because of the 2012 kidnapping, now all visitors to the volcano need to be accompanied by a team of armed guards. Unlike the Simien Mountains, where our scout / guard was merely a bureaucratic formality, we felt (sort of) safer having the guards in the this situation.

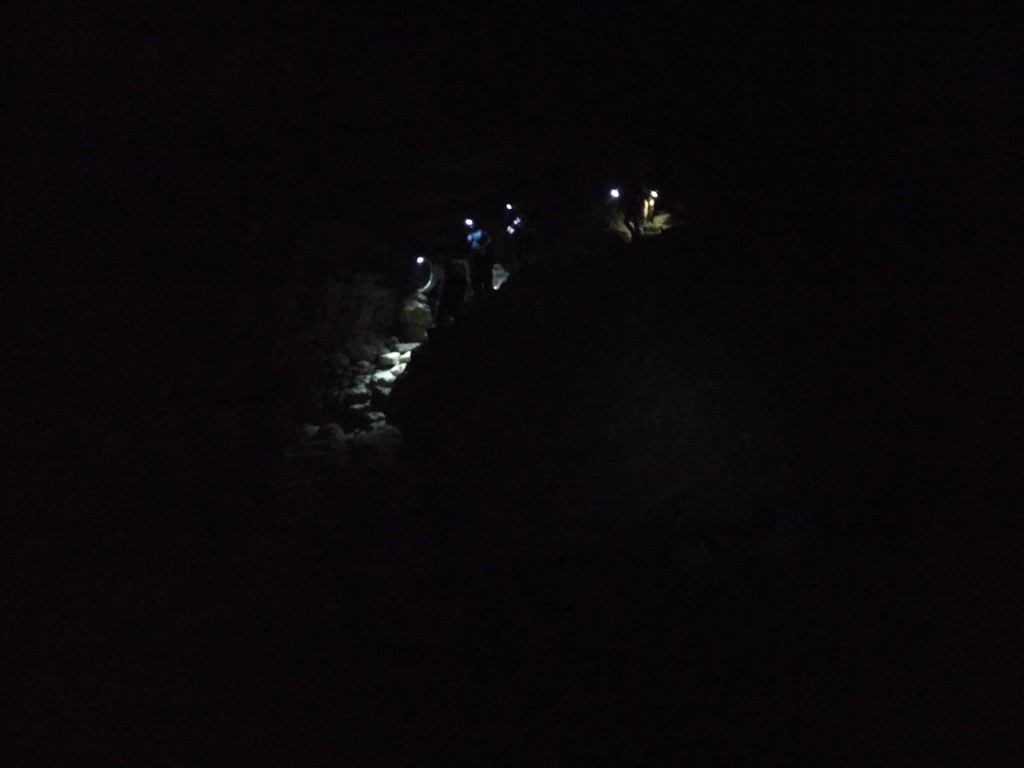

We ate an amazing dinner prepared by our fearless cook Merry and lamented the absolute lack of bathrooms at the flat, exposed site. At sunset we started the hike to Erta Ale, an active shield volcano, referred to by the locals as ‘the gateway to hell’. As we walked, under the light of a nearly full moon, the ground beneath our feet changed from sand and grass to lava rock, and we started to see a faint red glow in the distance. Once we reached the camp (which is located at the edge of the volcano’s caldera), we saw a scene that reminded us of the burn at Burning Man: a huge glowing fire with the silhouettes of people standing at its edge, spellbound.

Our guide sternly warned us to follow his steps ‘exactly’ and we carefully kept close behind him down a steep, narrow trail into the caldera. We happily trailed him while the light of the magma lake got brighter and we started to feel the heat.

As we climbed up to the edge of the inner crater, our feet crunched on and broke through the recently hardened lava rock. (We later learned that two weeks previous, the lava spilled over the edge of the inner crater and the tour group could only watch the lake from the camp, hundreds of meters away, at the edge of the outer caldera.) Our feet and legs felt like they were burning, when we passed spots where the heat from the magma below was venting through. When we came to a stop about 20 feet from the ~13000 square meter lake of boiling, bubbling fire, our minds were blown. Words completely fail the marvel of this experience. We both (and especially Jason, who is something of a pyromaniac) agree that this was definitely one of the most amazing things we’ve seen in our lives.

Everyone in our group stood at the edge of the crater, both mesmerized and terrified. At any moment, a splash of this ~2000-degree-Fahrenheit molten rock could splash up and kill us. A strong prevailing wind was blowing the across the lake, sometimes carrying pieces of lava over the lip of the crater, only 50 or so meters away from us. If the wind direction changed, we’d be right in the path of the flying lava. Needless to say, this experience would never be possible under the rigorous regulation we experience in the U.S. We both agree this was well worth the risk. After 40 minutes or so, our guide tore us all away from the lava lake and we walked back to camp, exhilarated, for a short sleep under the stars.

We woke up a few hours later and were happy to make one last visit back to the lava lake. On the hike back to the army camp, we began to realize that we were part of a huge, depressing problem: there is no management of trash or sewage at Erta Ale. At the campsite, there was a giant pile of plastic bottles and other trash, and there was no proper toilet, so there was human waste all over the place. On the walk back to the cars, we saw guides and scouts tossing their water bottles wherever and using the cracks in the lava as a garbage can. We picked up as many bottles as we could, but without an organized effort, this problem will only get worse. We talked to our guides about it, but everyone just shrugged and dismissed it as a problem too big to solve. If you ever decide to visit this beautiful spot, please send a message to the Ethiopia Ministry of Tourism and Culture to encourage them to set up a proper waste management system at Erta Ale.

After we left Erta Ale, we drove to a small village called Berhale, where we stayed with a kind family of seven. We hung out in their courtyard and ate popcorn and drank some more delicious coffee.

While chatting with others in our group, we realized many of us were interested in trying khat, a leafy green plant with a stimulant effect considered stronger than coffee but weaker than amphetamine. We convinced our guide to pick some up for us and gave it a go. The results were…anticlimactic. One of our fellow tourists put it best when she said: ‘it’s a whole lot of effort for almost no reward’. You have to constantly chew a large amount of mushy, stringy leaves for many hours in a row in order to get an effect similar to coffee. But it was still interesting to try.

While we tried out the khat in the back of the jeep, our drivers took us to another surreal landscape, the salt flats near Dallol.

We wandered around, admiring the form and aesthetics of the sulfate polygons and the salt lake, Lake Assal.

And then the guides surprised us with wine.

And an impromptu dance party, where they (tried to) show us how to dance Ethiopian.

As we danced, we watched caravans of camels go by, carrying loads of salt more than 50km to the nearest town.

Later, we visited a salt mine at Ragad, where men use chisels and sticks to cut ~10kg squares of salt and load them on camels. The men work up to twelve hours in the extreme heat, and make only a few dollars each day.

On our last day, we woke up early (after sleeping on cots under the stars in a village called Hamed Ela) to visit the Dallol sulfur springs and volcanic explosion crater or maar (a crater caused when an eruption causes groundwater to come into contact with magma). Dallol is an Afar word meaning dissolution – the magma-heated water moves through the evaporated soils, dissolving salt, potash (potassium carbonate) and other soluble minerals and creating hot springs that discharge brine and highly acidic liquid. Scientists have only begun to study the extremophiles living in this environment, and are hoping that doing so will help us understand how and if life might be possible on other planets.

The further we walked, the weirder the landscapes became.

Until finally we felt like we were on Mars.

Our guide pointed out the nearby potassium mines and made sure none of us fell in the toxic waterways.

We were sad to leave such a unreal place and hope to visit again someday. But, onward; we got dropped off at the tiny Mekele Airport,

where we were amused (and somewhat unsettled) to check out their flight schedule, written on a whiteboard. Then we hopped on a short flight to our last stop in Ethiopia, its capital Addis Ababa.

Reed, it looks like the two of you are having an amazing time! I am loving living vicariously through you!! Those photos of the potassium mines are incredible!

Pingback: 531360 Minutes, a Summary – babble.fish